The big news of month four was that I moved into my own apartment and I’m now living on my own. I lived with two different host families during my first three and a half months in Morocco: two months during training and then a month and a half once I arrived at my final site. Both families were wonderful and I understand why Peace Corps has volunteers live with host families. I learned more about Moroccan culture sitting in my host family’s living room than I ever could in a classroom, and being forced to use Darija every time I wanted to communicate did wonders for my language skills. My host family in Kalaa was invaluable my first few weeks in my site. They led my around town, took me to the store and my work and the hamam, and introduced me to their friends and neighbors. I would have never been able to find or furnish my apartment without them. However, by the end of December, I was getting increasingly ready to move out. I was ready to not have a curfew, to be to be able to do what I wanted without asking permission first, to eat something that wasn’t tagine and to be able to set my own schedule. I was ready to be an adult again.

The lack of a schedule was particularly difficult, especially once I got to my final site and no longer had the schedule of CBT to structure my ever-waking moment. Life with my host family was structured around the meals, but I never knew when those would be. Lunch was served sometime between noon and three, but I could never figure out a schedule. Whenever I asked, I was told “soon,” which could mean hours, and if I tried to skip lunch, my host mother would get upset, so I ended up sending all afternoon waiting around for lunch, regardless of what I wanted or needed to do that day. I was sick for most of December, and I lost my appetite and slept a lot. I would get home from work at 8:00 and go straight to bed without dinner, only to be woken up by my host mother barging into my room and waking me up to ask how I felt and if I was tired. I know they were acting out of kindness, but yeah, by January 1st, I was ready to have my own place.

I spent my first night at my new apartment on New Years Day. My apartment was almost entirely empty; all I had was a mattress on the floor and a loaf of bread to eat, and the loaf of bread was gift from my host family, but as soon as I finished hauling over my things and had shut the door behind my host family and was finally alone in my new home, I felt the tension that had been building up for the last few months start to melt away. Over the next week, I picked up a bed, another mattress (long story), a dresser, a bedside table, a stove and some cooking supplies. My place is still pretty bare, but it’s mine and I’m slowing filling it up.

I was worried that moving into my own place would mean that I would be cut off from the community. As frustrating as living with a family was, my host family was a great way to meet people and be an active part in my community, especially since Kalaa is big enough that I’ll never know everyone. Plus, I have a tendency to be an introvert, and spent the last few weeks with my host family thinking longingly about locking myself in my apartment and refusing to talk to anyone for at least a day. I occasionally have to get dressed before leaving for work at 6:00 because it’s the first time I’ve left the apartment that day, but I’m doing okay. I live in the building next to my host family, which means I see them every day, and I still live near everyone they introduced me to in the neighborhood. I stop by my host family’s house after work at least once a week, and go over for lunch of Couscous Fridays. My downstairs neighbors have taken it upon themselves to make sure I’m fed, and I’m invited over for tea or dinner a couple of time a week. Apparently, they’ve heard that I can’t make bread, which clearly means that I can’t cook. I’ve also had a few invitations for dinner from my students at the Dar Šabab, so I’m still being social.

I started travelling around Morocco during month four. During PST, I didn’t have enough time for a decent night’s sleep, much less to do any sightseeing, and we were encouraged to stay in our sites for the first few months of service. I spent Thanksgiving at site, but Christmas is more important, and I celebrated by going to Marrakesh with my sitemates and some other volunteers from my staj. It was my first trip to Marrakesh, which is an hour and a half south of Kalaa, and I loved it. We stayed in the medina, just off the main square, and it was a riot of people and performers and back alleys full of tiny stalls selling everything under the sun. It reminded me of Seoul, especially the warrens of Namdaemun or behind the main strip Gangnam, only with less neon. (Most of my comparisons to Korea end with “only with less neon.” This restaurant reminds me of one in Seoul, only with less neon. Trash pickup in Morocco reminds me of trash pickup in Korea, only with less neon. There’s a lot of neon in that country.)

Then, two weeks later, I spent the weekend with my stajmates Carrie and Bethany in their site, Boujad. It was my first time travelling alone in Morocco, and my first time taking the bus. There are a couple of different types of busses in Morocco. There’s CTM and Supratour, bus lines similar to Greyhound or Megabus in the US. They’re more expensive, but the busses are nicer, the routes are more direct and you’re guaranteed a seat. Then there are the small intercity busses, which are called

kar by Moroccans (no possibility for confusion there) and

souq busses by PCVs. They’re smaller and less comfortable – more like a school bus – and they take longer because they stop at every little village or random pile of rocks by the highway where someone wants off. They are, however, cheaper, and run more frequently.

My plan was to take Supratour to Beni-Mellal, a large city near Bejaad, and meet Bethany there. I knew there was a Supratour station in Kalaa, Bethany knew where the Supratour station was in Beni-Mellal and I could look up the bus schedule online. Plus, I’d stories from other volunteers of standing for hours among vomiting children and livestock on

souq busses, and Supratour wasn’t

that much more expensive. Of course, like many things in Morocco, finding the bus station took a committee and many, many more hours than something as simple as finding a bus station should.

First, I asked Hanan, one of my host sisters, if there was a Supratour station in Kalaa. It took Hanan a while to figure out what I was saying, because I say Supratour like an American and I should be saying like the French, but she confirmed that there was a station and even gave me vague directions. Then, during Couscous Friday, I asked the rest host family if they knew where the Supratour station was, but they did not. In fact, they weren’t even sure that there was a Surpatour station in Kalaa. On Saturday, the day before I was suppose to leave, I asked some of my students at the Dar Šabab if THEY knew where the Supratour station was, and finally found a friend of my friend Hayat who was in the drama club and not even one of my students and knew where the station was. The only problem was the station was on the edge of town.

HAYAT: You can’t walk there! It’s too far.

CAIT: I don’t even know where it is yet.

MUSTAFA: It’s very far away. It’s too dangerous to walk there. And you need to buy your ticket in advance.

CAIT: Still don’t even know where the station is, so kinda a moot point.

MUSTAFA: The station might still be open.

HAYAT: I will drive you there now! We can buy your ticket.

CAIT: Hurray! Someone’s going to tell me where the station is.

I stopped to tell the

mudir (director) that I was leaving, and Hayat told him about my trip.

MUDIR: You’re going to travel alone?

CAIT: That’s the plan.

MUDIR: You can’t do that. It’s too dangerous.

CAIT: Right, this is Morocco and doing anything alone, including walking next door, is considered to dangerous. Thank you, but I’m pretty sure I’ll be fine.

HAYAT: He’s right. It could be dangerous.

CAIT: Okay, potentially dangerous travel would be that time my tuk-tuk was waved down a deserted dirt path by Cambodian soldiers carrying machine guns at 4:30 in the morning. Taking a major bus line and being met by a friend at the bus station in a country where I can speak the language isn’t dangerous.

EVRYONE: You can’t speak Darija.

CAIT: This ENTIRE CONVERSATION has been in Darija. I know my Darija isn’t pretty, but it’s more than sufficient to buy a bus ticket. Plus, I’ve only been studying for four months. I think I’m doing pretty good.

MUDIR: It’s dangerous. My brother-in-law is going to Beni-Mellal tomorrow. He will drive you.

CAIT: Really, that’s not necessary. So close to finding out where the bus station is.

MUDIR: I’ll call him now.

Luckily, the brother-in-law was at the mosque praying, and I was able to convince Hayat that, no really, the bus was the better option. The bus station was closed, but Hayat drove me back the next morning to help me buy my ticket. According to the website, the Supratour bus to Beni-Mellal left at 11:00, but when we showed up at 10:30, the ticket seller was shouting “Beni-Mellal, Beni-Mellal!”

“Why yes,” I said. Hayat bargained for my ticket, told the bus driver exactly where I was going and to make sure that I got off at the right stop, and made me promise that I was being met in Beni-Mellal and would call if I had any problems. After the drama of finding the bus, the ride itself was uneventful through some truly gorgeous countryside. I had two seats to myself, and there were no chickens or vomit anywhere to be seen, although I did see a group of camels being herded down the highway It was only when I arrived in Beni-Mellal at a completely different bus station than I thought I would that I realized that after all that trouble to find the Supratour station, I had ended up taking a

souq bus. Oh, Morocco.

The rest of my trip was also fun. I more or less tagged along as Bethany and Carrie went about their normal weekend. We split a roast chicken and bottle of wine for dinner and stopped by what Bethany has dubbed the sugar carts, wheeled carts full of sugary pastries from a local bakery, for desert. Breakfast was

miliwi, fried bread, slathered with cheese in their courtyard, then we went to the hamam for our weekly bath and to their tutor, Lamia’s, house for a lesson. I sat in on the lesson, taking notes, and answering the occasional question. At the end of the lesson, we were talking about regional dialects, and I mentioned that even though Kalaa was only about 100 km south of Boujad, I could tell a distinct difference between the way people speak, much to Lamia’s confusion.

LAMIA: Where?

CAIT: Kalaa Sraghna. Big town on the road between Beni-Mellal and Marrakesh.

LAMIA: You’ve been to Kalaa Sraghna.

CAIT: Why yes I have.

LAMIA: … Why?

CAIT: I live there.

LAMIA: … Why?

CAIT: We don’t really get a choice. Peace Corp throws darts with our names on them at a map of Morocco and we go where our dart lands.

LAMIA: Peace Corps?

CAIT: I’m in the same organization as Bethany and Carrie. That’s why I live in Kalaa.

LAMIA: Oh, I thought you were visiting from America.

CAIT: Nope, just up for the weekend.

LAMIA: That explains why you know Darija.

CAIT: Yeah…

Bejaad has a large medina, the old walled part of the city, and Bethany and Carrie live in the middle of it. Their neighborhood is cool – full of history and traditional and the potential to make a wrong turn and get hopelessly lost forever. It was great to see Bethany and Carrie, and now that I know where the bus station is (I walked home, and it is neither dangerous nor that far), I’ll keep traveling!

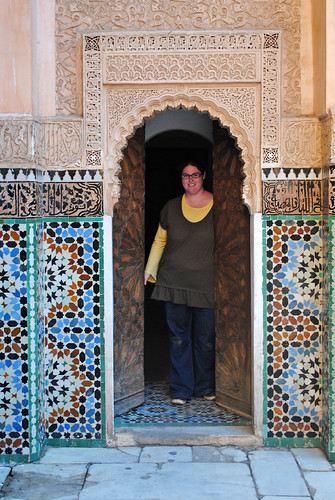

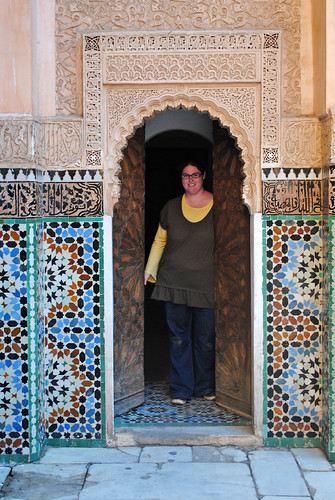

Top:Bright teal ovens stacked in front of one of the stuff shops in town; Middle: The day after Christmas at the Madrasa Ben Youssef in Marrakesh (left); Cranes nesting in the minaret of one of the mosques in the Boujad medina (right); Bottom: Hanging lanterns in the Marrakesh souq.

Souq can be a little intense, which is one of the reasons it took me so long to go. Kelaa’s souq is huge, and is packed with vendors and people and cars and livestock and donkeys. The first time I went, I got a little lost. I can see souq from my balcony, so my sitemate Lucia and I walked over, only to find ourselves in a maze of vendors selling used clothes, power cords, bike handles and kitchenware. There’s an entire row of stalls selling only different types of flour. There are tents with heaping bags of brightly colored spices and an entire section full of chickens, turkeys and sheep in all manner of decapitation. There are guys with music carts blasting Arabic pop music, and vendors selling popcorn, chickpeas and meat kababs. Lucia and I wandered lost for a good twenty minutes before finding what we were looking for, the produce section. The produce section is a couple of blocks large at the far end of souq where farmers from the area spread their produce out on tarps on the ground and sell them. The selection is limited during the winter, but I can’t wait to see what’s available this summer.

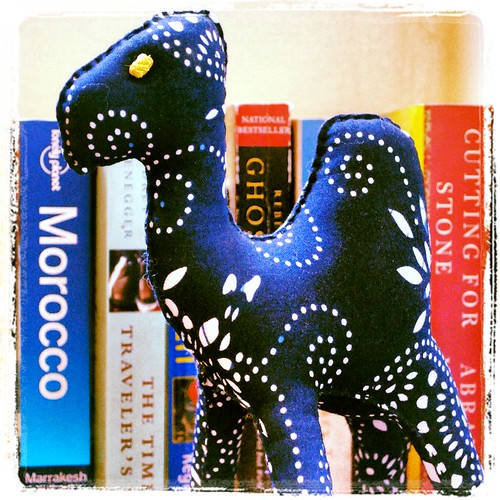

Souq can be a little intense, which is one of the reasons it took me so long to go. Kelaa’s souq is huge, and is packed with vendors and people and cars and livestock and donkeys. The first time I went, I got a little lost. I can see souq from my balcony, so my sitemate Lucia and I walked over, only to find ourselves in a maze of vendors selling used clothes, power cords, bike handles and kitchenware. There’s an entire row of stalls selling only different types of flour. There are tents with heaping bags of brightly colored spices and an entire section full of chickens, turkeys and sheep in all manner of decapitation. There are guys with music carts blasting Arabic pop music, and vendors selling popcorn, chickpeas and meat kababs. Lucia and I wandered lost for a good twenty minutes before finding what we were looking for, the produce section. The produce section is a couple of blocks large at the far end of souq where farmers from the area spread their produce out on tarps on the ground and sell them. The selection is limited during the winter, but I can’t wait to see what’s available this summer. In late January, I went to Marche Maroc for a day. Marche Maroc is an artisanal craft fair run by Peace Corps and USAID. It’s held in bigger, touristy cities like Fes, Marrakesh and Essaouira, and gives artisans, mostly women working with Small Business Development PCVs in smaller, rural sites, a chance to sell directly to customers. I’m not SBD and I don’t work with any artisans in Kalaa (yet), but the January Marche Maroc was in Marrakesh, only two hours away from Kalaa, so I went. Technically I went to help, and I did spend a half hour hauling goods and furniture to the storage space after the fair, but mostly I helped out with my wallet. I bought a small rug, an adorable stuffed camel and a pair of earrings as a belated Christmas gift for my sister. I also spent some time enjoying Marrakesh, and got lost in the souq, bought a pair of Aladdin pants, and had a very expensive dinner at an Indian restaurant and a terrible (yet expensive) beer.

In late January, I went to Marche Maroc for a day. Marche Maroc is an artisanal craft fair run by Peace Corps and USAID. It’s held in bigger, touristy cities like Fes, Marrakesh and Essaouira, and gives artisans, mostly women working with Small Business Development PCVs in smaller, rural sites, a chance to sell directly to customers. I’m not SBD and I don’t work with any artisans in Kalaa (yet), but the January Marche Maroc was in Marrakesh, only two hours away from Kalaa, so I went. Technically I went to help, and I did spend a half hour hauling goods and furniture to the storage space after the fair, but mostly I helped out with my wallet. I bought a small rug, an adorable stuffed camel and a pair of earrings as a belated Christmas gift for my sister. I also spent some time enjoying Marrakesh, and got lost in the souq, bought a pair of Aladdin pants, and had a very expensive dinner at an Indian restaurant and a terrible (yet expensive) beer.